The task of ensuring safe passage for mariners has always been a challenge. The United States government began using lightships as a means to warn mariners of dangerous shoals or mark shipping channels/entrances to major ports. The usefulness of lightships proved to suit a number of necessities. Lightships could be anchored in shallow waters where shoals often shift which prevented the construction of a fixed structure. They could also be anchored off shore in deeper waters, enabling them to indicate shipping lanes for general oceanic traffic. Another benefit to lightships was that they were not fixed structures and were able to be repositioned or relocated to better serve the particular need of each station.

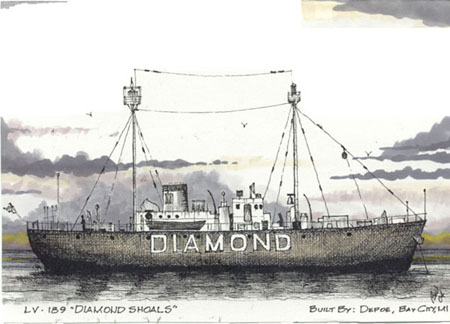

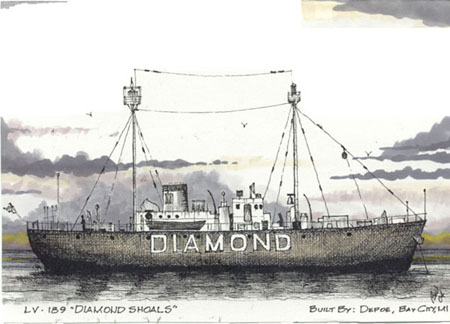

Lightships marked their particular station in a number of ways. Each station was given a specific name, such as Overfalls, Huron, or Nantucket. This name would be painted on the hull of the ship so that the station could be identified during the day, just as lighthouses have their own daytime characteristics (or paint scheme). At night, the light of the lightship would not only signal the location of the ship, but also have its own flash pattern or nighttime characteristic, making it possible for mariners to identify which station they were approaching. Likewise, lightships were eventually equipped with sound devices, such as foghorns, to be sounded in times of low visibility.

The service of lightships began in 1819, John Pool was contracted to build the first lightship. Ready for service in the summer of 1820, the lightship began its service near Willoughby Spit, VA. Its purpose was to aid shipping in the Chesapeake Bay. This particular location left the boat well exposed to the weather. Storms and high seas forced the lightship to be moved to a safer location off Craney Island, in the vicinity of Norfolk, VA. Less than a year later, lightships began marking four dangerous shoals in the Chesapeake, but it wasn’t until 1823 that a lightship was stationed in open water off Sandy Hook, NJ.

By 1838, Congress established eight lighthouse districts. The Atlantic coast was divided into six districts and the Great Lakes comprised the two remaining districts. Each district was assigned to a Navy officer who was responsible for conducting overall inspections of stations in the district. As reports begin to come in, a number of problems began to surface. Reports outlined defective equipment, untrained personnel and poor morale among personnel, yet no action was taken at this time to correct these issues. Finally, in 1851, Congress became aware of the flaws in the lightship program and sent out a team of competent inspectors to assess the situation. Their report concluded that many ships were poorly maintained, the lighting equipment was inadequate to serve their designed purpose, crews were not properly trained, and supplies were meager. Along with the report, a number of recommendations were made and would later prove to be useful.

A year later, in 1852, the report led Congress to form the Lighthouse Board. The board took immediate action, given the recommendations of the report, which were to upgrade equipment and technology, and to revise contracting procedures. The organizational hierarchy was also overhauled. The Atlantic coast was now divided into seven districts, two districts on the Gulf coast, one on the Pacific coast, and two on the Great Lakes. 1855, lightship design became more standardized, a number of new lightships were constructed, new stations were added, and illumination equipment was being used on the existing vessels. Fog signals were installed and being used, and methods of marking one lightship from another became more standardized. At this time, attempts were also made to improve the skills of the crews. Only being paid $.20 per day, wages, accommodations, and food remained sparse.

Although the Lighthouse Board brought about vast improvements to lightships, it was disbanded in 1910. Lightships were then placed under the direction of the Bureau of Lighthouses, where they finally found their truly useful place as effective aids to navigation. By 1939, lightships were assigned to the Coast Guard when it took over control of aids to navigation. By this time, the number of lightship stations had been reduced from 116 to 30 and the number of stations continued to decline until 1983 when they were finally removed from service. These ships were replaced with oilrig type towers or large floating buoys which were cheaper and easier to maintain. Today, a few lightships still remain, some being lovingly restored and opened for the public to tour and learn about this piece of our maritime history.